The modern-day remnant of Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground has 422 headstones and 169 footstones out of the thousands it probably once held. Between 5,000 and 6,000 people were once laid to rest there. Of the remaining stones, more than 230 have the name of a woman carved on them. A recent project that documented and photographed the headstones revealed at least 234 distinct women with some surviving stone.1

Most people interred in the burying ground, male or female, Black, white, or Native, have no extant headstone. Many would have had a marker of some kind, but it has now disappeared. The grave was simply a final resting place for one’s remains in reformed Christianity, not hallowed ground, and so every kind of person could be laid to rest in the town cemetery. Epitaphs frequently extolled one’s character, but they could occasionally condemn it or simply say nothing at all.

Half of the English migrants to New England were female.

The Ancient Burying Ground’s tall obelisk to the Founders of Hartford, erected in 1837 and replaced in 1986, honors only the men. It was originally built at a time when the role of women in society had a secondary place. The obelisk ignores the half of the English migrants to New England who were female with the exception of two widows, Dorothy Chester and Mary Betts.2 Puritanism introduced a new idea of the family, in which female piety was central to social cohesion, and in which the good wife was a husband’s helpmeet.3 It was a joint enterprise. It was also an enterprise that often relied on servants in the home.

As Native women became forced household servants after the Pequot War of 1637, and African women joined them over the next century and a half, the colonial household became a place of occasionally competing and sometimes amalgamating traditions. Native women, like Sarah Onepenny the Elder, could be both an esteemed elder among the Wangunk and a servant-nurse in the Whiting house. Whether a Puritan helpmeet in charge of the household or a woman of color forced by circumstance to serve her, the focus of this project is to bring women interred in the Ancient Burying Ground to the forefront of our picture of Hartford’s past.

Areas of Study

Motherhood

Motherhood was a valued . . .

Widowhood

Thirty-five headstones . . .

Poverty

One wonders about . . .

Women of Color

There were 107 women . . .

Native Women

On a May day in 1713 . . .Names

Naming is important in all societies, and the Ancient Burying Ground records some spectacular names, such as Delight Wattles or Azubah Warner. Azubah was named for a Biblical figure, the wife of King Asa and the mother of King Jehoshaphat of Israel, but her name meant “desolation.”

Photo, right: Azubah Warner’s stone

More frequent were names that, like Delight, reflected a state of being: Hope, Experience, and Thankful. The most common names, however, were Mary, Sarah, and Abigail. Of the extant stones, 49 have the name Mary, 30 Sarah (or Sary), and 17 Abigail. Few women’s names in the burying ground are anything other than English, but the Dutch name Willemyntje is coupled with the English surname Bassett. The Bassetts were refugees from New York during the American Revolution, which like Hartford had both Dutch and English settlers.4

Photo, below: Willemyntje Bassett’s stone

Motherhood

Motherhood was a valued status for women. Mothers were “guardians, interpreters, and inculcators of Puritan culture,” according to historian Amanda Porterfield. Within the Puritan family, they helped instill in their children the tenets of reformed Christianity.5 Children expressed love for their mothers, and the mother-child relationship often had tender references on gravestones or in elegies.

Image, right: “Poets Corner,” Connecticut Courant, January 12, 1773

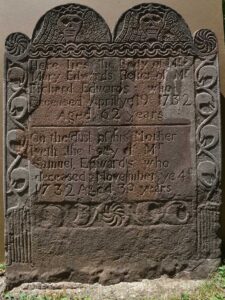

The gravestone pays tribute to mothers in various ways.

- Erected by George Beach to the Memory of his Mother, Mrs. Lucy Whitman.

- Samuel Edwards, who died as young man of 30, is buried “On the dust of his Mother.”

- William Burr, who was interred with his mother.

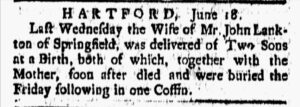

- While it is rare to see a grown man buried with his mother, but when mothers died in childbirth, their infants were often buried with them.

Widowhood

Thirty-five headstones bear witness to widowhood in the Ancient Burying Ground by including in women’s epitaphs the word “relict” which meant widow. A widow did receive legal protection through her dower right, an entitlement to one-third of her husband’s estate for the duration of her life.6 The heirs’ inheritances were made conditional upon their support of the widow. An examination of records in the Hartford district of Connecticut between 1638 and 1681 revealed that husbands and courts protected their “relicts,” but few gave her control of the estate. Husbands’ wills often strictly curtailed their widows’ control over property, preferring sons or grandsons when they came of age. Widows rich and poor often saw a decline of status and material comfort. A husband’s debts sometimes ate up the bulk of an estate. The widow’s third, to which she was entitled by law regardless of a husband’s disposition, was only occasionally supplemented with an annuity.7 While there were widows with means, many faced a more difficult life than they had known or could know as wives. Many remarried under these circumstances. New England generally had the lowest rate of female householders in 1790 of any region in the country, although cities in New England had higher incidences than elsewhere.8

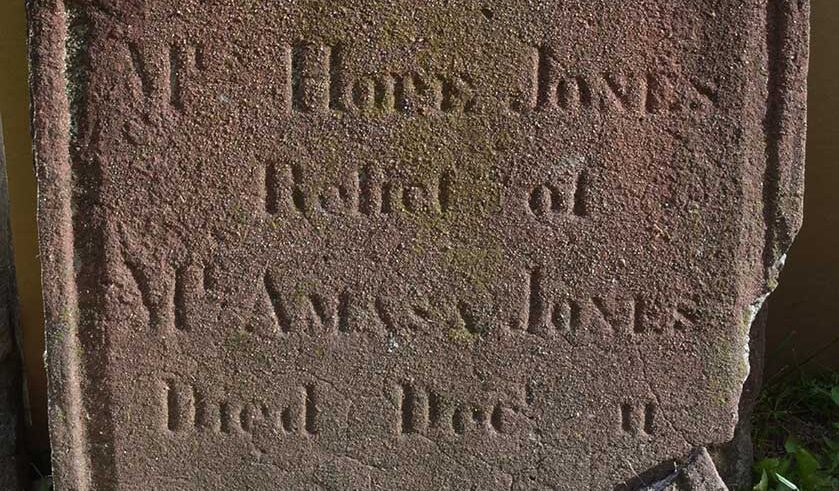

Photo, left: Hope Jones’ Headstone

Poverty

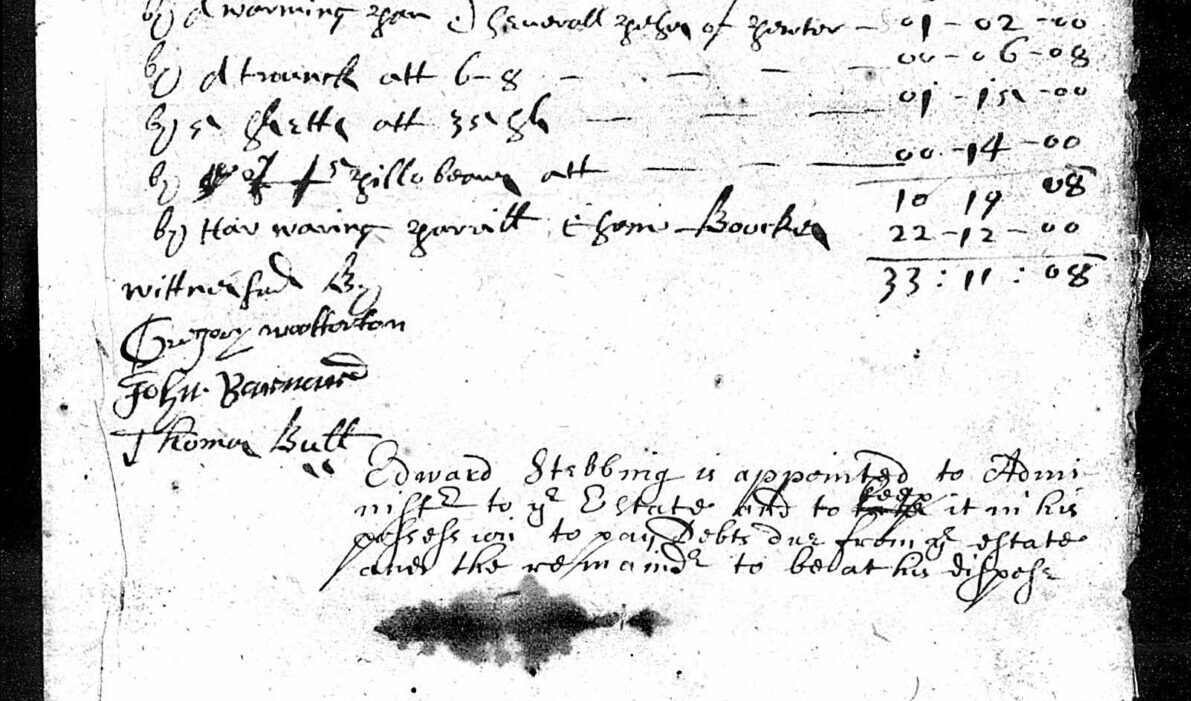

One wonders about the life of Dorothy Chester, who died impoverished in May, 1662. Her inventory shows an estate worth just a little over 33 pounds containing blankets and a warming pan and some sewing implements. A biography on the website of the Founders of Hartford says she was already widowed five years when she emigrated to the Bay Colony in 1633 and later followed her brother Thomas Hooker, the prominent minister and founder of Hartford. She never remarried, which was unusual for a woman of her age and status. Genealogies and biographies are silent about the meager contents of her household.9 Dorothy’s son Leonard predeceased her in 1648. In his will he left her only 30 pounds, despite having a substantial estate.10 She appears to have sold her land over time – one and 1/5 acres in the North Meadow to Nathaniel Richards, a one and 1/5 acre parcel on the east side of the Connecticut River to William Spencer, and six acres, some meadowland, and swamp to William Pantry – probably to make ends meet.11 The impoverished status of Dorothy Chester, a woman of status among the colonists, allows us to infer the grinding impoverishment of single women without her status whose names are not reflected in the remaining headstones.

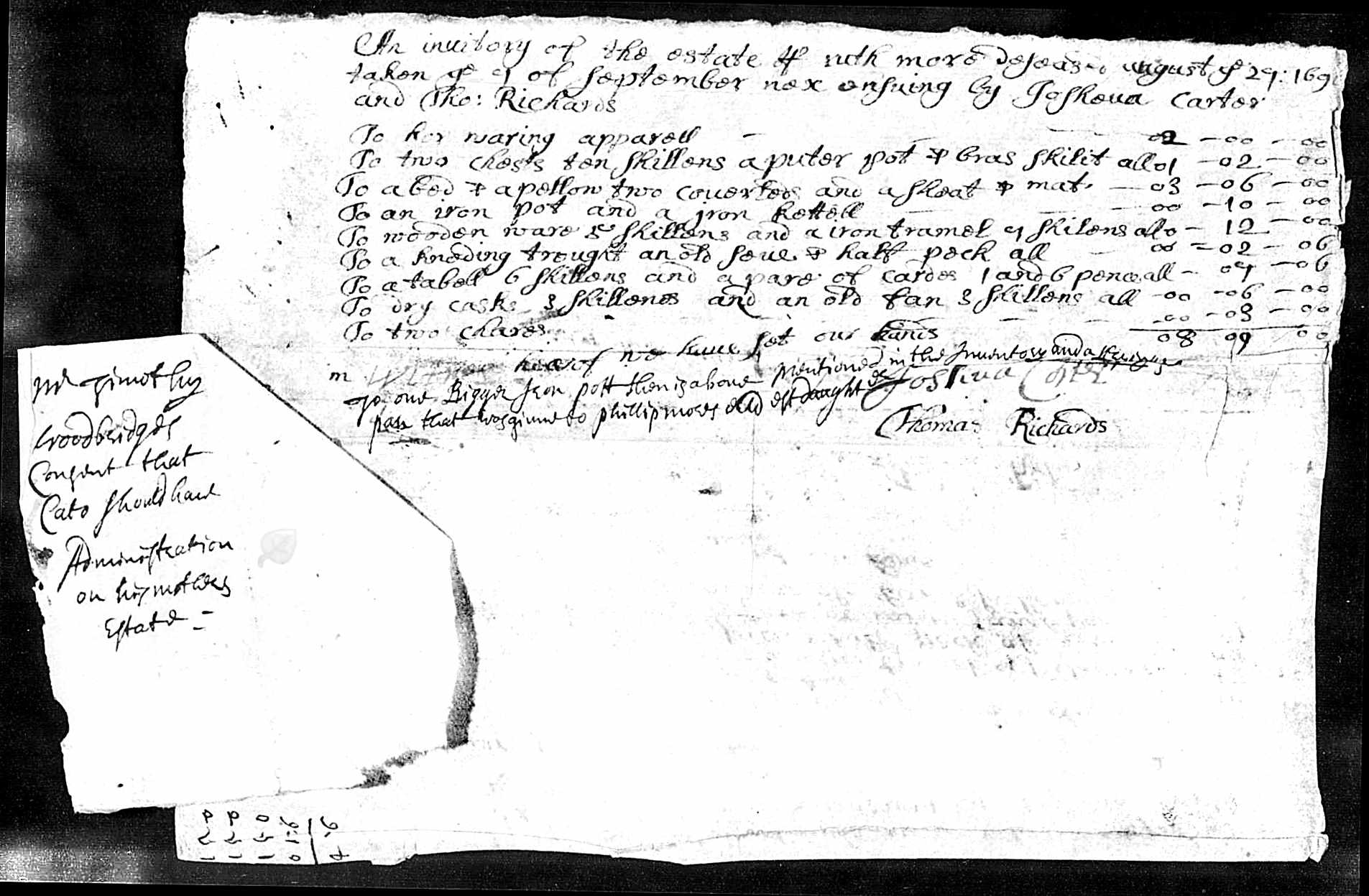

Image, right: Dorothy Chester’s inventory, 1662

Women Who Wrote Wills or Whose Inventories Were Taken

Quite a number of women, mostly widows, left wills, both written and oral, or had probated estates recorded by the court. Probate Court records are a font of information about the lives of women interred in the Ancient Burying Ground. Women’s literacy, measured by the ability to sign one’s name, rose in Windsor during the colonial period and probably elsewhere in Hartford County as the result of a 1690 law requiring schools to see that everyone could read.12 Literacy enabled women in many ways, including using the power of a will to carry out their wishes after death.

Women’s inventories, lists of possessions at death created for the Probate Court, reveal the details of everyday life. One woman, Sarah Watters, made a point of leaving her daughter Mary a precious silver spoon in her will. Yet her inventory lists a number of objects: a book by Increase Mather and other books of sermons, a featherbed and pillowcases, many handkerchiefs some of which were silk, a striped petticoat, a damask frock, and Holland shifts.13 Dozens of women left wills or had probated estates, including Native, African American, English and French women. They had all levels of wealth. What united them was a sense of wanting to ensure their heirs received what was precious to them.

Image-left: Sarah Watters’ Will, 1736

Women of Color

In 2018 the Ancient Burying Ground Association commissioned research into the Native, African, and African-American people buried in the Ancient Burying Ground. That research led to “Uncovering Their History” which comprises a database of all currently known information of the people along with narratives, profiles, family trees, and relationship trees. There were 107 women and girls of color identified as likely to have been buried in the Ancient Burying Ground. The database includes all records including those the researchers marked “Slightly Confident,” “Somewhat Confident,” and “Highly Confident” of burial in the Ancient Burying Ground. This figure of 107 excludes those persons of color whose sex was unknown. (To see the fullest picture possible of these 107 women, see the Uncovering Their History website.)

Enslaved women of color present in households when their “owners” died were mentioned in their probate inventories and wills. In 1732, Anne Hosmer inherited an enslaved woman among other goods her husband left her, in addition to her dower. The will does not specify if the “negro woman” is any relation to the boy, Ceasar, also willed to her by her husband. Such relationships often did not matter to masters.

From the perspective of the master, the unnamed “negro woman” mentioned below, along with her unnamed children, were part of the estate’s chattel, like the household goods, the cows and the mare.

Last Willl

Thomas Hosmer, 1732

I, Thomas Hosmer of Hartford, do make this my last will and testament: I give unto my wife, Anne Hosmer, 1-3 part of all my lands in Hartford for her

improvement during life, also 3 rooms (one lower room and two chambers) in my dwelling house, which she shall choose, the third part of my cellar, and the 1-3 part of my barn, for her use during her widowhood; also give her 1-3 part of my

household stuff, 1-3 part of my stock of cattle and other creatures, and my negro woman, to be at her own dispose forever. Likewise I give her one of my negro boys, viz., Ceaser, for her service so long as she remains my widow. If she marry, the boy I give to my son Stephen …14

Last Willl

Samuel Woodbridge, 1746

I give unto my wife, Content Woodbridge, all those household goods and estate which I had with her when I married her. I say all that remains, of whatsoever denomination, and all the household goods which have been brought into the house since our marriage, and the negro woman and all her children, which are now my property, and all the debts due to me in Rhode Island, and œ100 money out of a bond due to me from my son Deodat Woodbridge, and 1-3 part of my moveable goods belonging within the house, besides those before given her, and two cows and a black mare I bought of Matthew Beel. And further I give to my wife the use of 1-3 part of my dwelling house and barn, and 1-3 part of all my improveable lands, during her natural life.

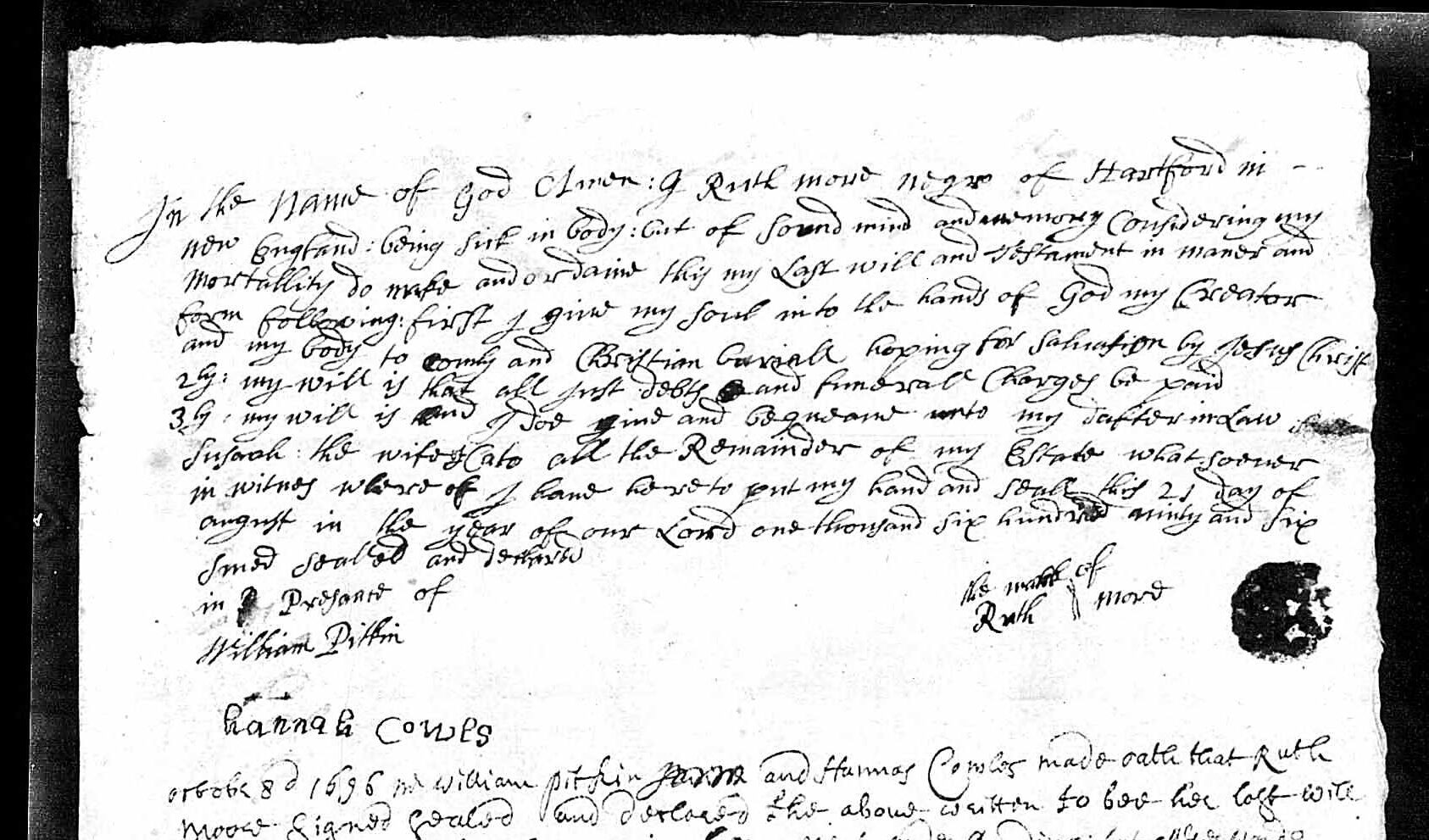

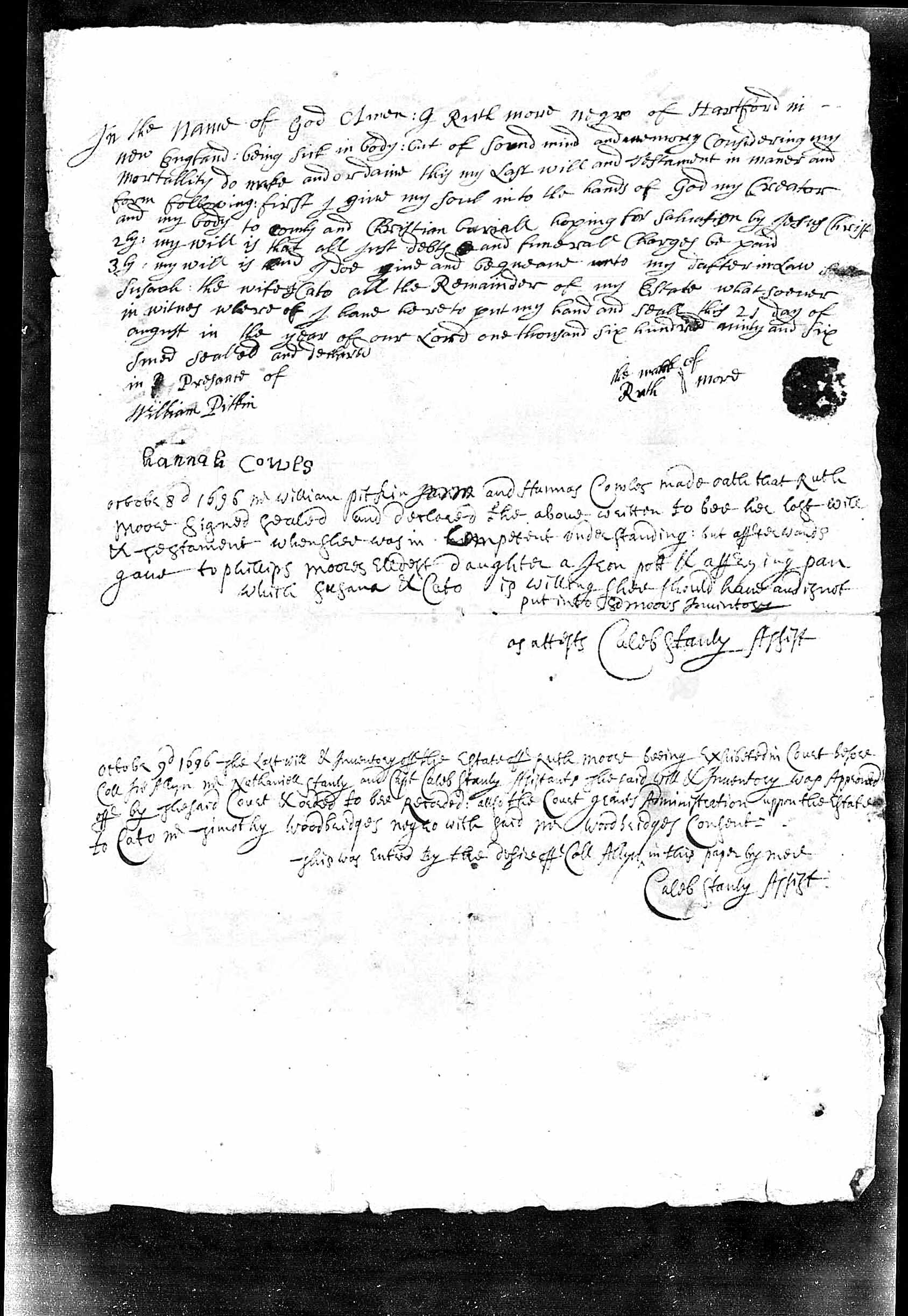

Yet not all women of color interred in the Ancient Burying Ground, even those of African descent, were enslaved. Some free women left wills. Ruth Moore (also spelled More), described variously as “negro” and “mulatto,” left a will in 1696, the earliest of any women of color in Hartford and perhaps the earliest in the colony. Ruth and her family were Christians and some of her children and grandchildren joined the First Church in Hartford as members in communion. Ruth’s will is like that of many housewives in the colony, specifying to whom she wants her best frying pan (a “bras skillet”) to go to, for example.

Images-right: Ruth More’s will and inventory

Native Women in Hartford

On a May day in 1713 in Hartford, Connecticut, Sarah Onepenny the Elder lay on her deathbed. She was surrounded by her three sons, Siana, Cushoy, and Nanamaroos, and her sister Hannah Onepenny. Also present was Mary Whiting, the twenty-five-year-old daughter of Col. William Whiting, an important magistrate and military leader. Sarah Onepenny told her listeners that all her land in the South Meadow in Hartford, especially a small parcel of three to four acres by the wigwams, should go to her grandson, Scipio. She told her sons to sell a small piece of meadow land in Middletown to pay her debts. The nuncupative (oral) will, probated in Hartford almost certainly at the behest of William Whiting, called her by an anglicized name, Sarah Onepenny, and contained no mention of her sons, but documents in Middletown complement the Hartford record.16 Sarah Onepenny was a sunksquaw of the Wangunk, a woman of status and importance, and she was also the servant of William Whiting, probably a nurse who cared for his daughter as she grew to womanhood. As Sarah Onepenny’s will shows, Wangunk women maintained their land and wigwams in Hartford’s South Meadow.

Native women were part of the fabric of life in Hartford, as servants in colonial homes or as free Native women who came to Hartford for market days and court appearances. Waisoiusksquaw (the wife “squaw” of Waisoiusk), was indicted for killing her husband by disemboweling him with a butcher knife and brought to trial in Hartford in May, 1711. She was sentenced to die on May 11 by a mixed jury of English and Indigenous men.17

Women and Enslavement

Hartford was home to hundreds if not several thousands of enslaved people in its first 175 years, and while men are most often named as enslavers, wives, widows, and single women claimed both Native and African women as their property. Ann Morison, the wife of Dr. Normand Morison, benefitted from her husband’s engagement in the transatlantic slave trade.

Photo-right: Ann Morison’s stone

Ann’s epitaph says she spent her life in “Faithful Service to God & her Generation.” Yet a sixteen-year-old girl named Chloe took care of the hall room in her house. A family consisting of Old Exeter, a woman named Chloe, and a 20-month old boy named Hercules and individual enslaved people named Hanabell, Sylva, Flora, Exeter, Rose, and Sambo staffed the Hartford home. Her husband owned 7/16ths of a schooner that made trips to West Africa and returned with enslaved people to work on farms in places like Bolton.

Some women manumitted the enslaved people left to them by their husbands or sons. Anne Foster Buckingham Burnham inherited people from her father, her husbands, and her son. At her death, she freed the five enslaved people in her household, Paul, Cato, Zipporah, Nunny and Prime, bequeathed to her by her son, Joseph Buckingham, Esq. In her will she gave Cato, Paul and Prime their own parcels of land of about eight to ten acres each, and she gave Zipporah and Nunny £10 apiece. This meager sum would not have given any financial security to the women. Since Burnham was the sole survivor of her nuclear family, she gave the rest of her property and belongings to her extended family and the churches in Hartford. She may have manumitted the enslaved people because there was no one to leave them to, or she may have wanted to set them free. Zipporah eventually died of dropsy at the age of 80 and was buried at the expense of the town.18

Photo-left: Normand Morison’s inventory

Freedom was precious, and to Sally Cuff, who lived in the household of one of Hartford’s richest men, John Haynes Lord, it was worth the £100 she had to pay him. She was the child of enslaved parents, Coffee, who may have come from Antigua, and Hannah. Her mother had been valued at £20 in an inventory taken when she was young. Sally was baptized in August, 1768 with another girl named Dinah. She freed herself in the summer of 1782, just two years before Connecticut enacted its gradual emancipation law. The record of Sally’s purchase of herself appears in volume 4 of the Hartford Land Records. Sally and her parents spent their lives engulfed by the Lords and Woodbridges, two prominent, wealthy families joined together in marriage. Sally’s self-purchase equaled the purchase of three young enslaved people. It was a huge sum.

Photo-right: Anne Burnham’s will

THE WOMEN IN HARTFORD’S ANCIENT BURYING GROUND

Conclusion

Alice Morse Earle, a still popular nineteenth-century antiquarian whose books are still sold in museum gift shops, documented the material culture and daily lives of colonial settlers, especially women and children. She captured certain material realities of kitchens, taverns, town squares, and even jails, but her books allude to people of color only in small anecdotes, usually about disciplinary matters. A century and a half after her death, we still have an incomplete picture of colonial life, though much more research has been done on women of all backgrounds. It is sometimes hard to picture the Hartford street of 1750 as one filled with people of many ethnic backgrounds—European, African, Caribbean, and indigenous.

The Ancient Burying Ground’s history is a part of that picture. Newspaper, probate, and church records help flesh out the stories behind the gravestones of white women interred there, as well as those who lack markers whether they were colonists, Natives, or of African descent. Time and modernity have encroached on the size of the Ancient Burying Ground (once six acres, now a little over one acre). The colonial Hartford housewife was not just English. She could also be Igbo or Angolan, or Wangunk or Pequot, or a combination of all of these. Free or enslaved, women worked side by side, but their status determined their roles. In law, one’s freedom followed the status of one’s mother. Often women’s husbands, or their lack of husbands, determined their material status. Although most women attended services at the Congregational meetinghouse, over time Anglicans and Baptists made inroads. In the early nineteenth century, African Americans formed their own church on Talcott Street. Women shaped the early city of Hartford socially, commercially, and religiously.

About the author

Dr. Katherine Hermes earned an A.B. in History from the University of California at Irvine; a J.D. from Duke University School of Law; and a Ph.D. in Colonial American History from Yale University. She has taught early American history at the University of Otago in New Zealand (1992-1997) and at Central Connecticut State University (1997-2022), where she also served as Department Chair, and is now Professor Emerita. She is currently publisher of Connecticut Explored magazine, a non-profit history publication produced for readers interested in Connecticut’s past. She has created and been involved with a number of digital public history projects, including “Uncovering Their History: African, African-American and Native-American Burials in Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground, 1640-1815,” for the Ancient Burying Ground Association, which won a Connecticut League of History Organizations Award of Merit in 2020.

Footnotes

1ABGA Photograph Inventory, and Learning from the Gravestones, https://ancientburyingground.com/burials/surviving-stones/.

2Virginia DeJohn Anderson, New England’s Generation: The Great Migration and the Formation of Society and Culture in the Seventeenth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 21.

3Amanda Porterfield, Female piety in Puritan New England: the Emergence of Religious Humanism. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 13, 32.

4William Hosley, By Their Markers Ye Shall Know Them: A Chronicle of the History and Restorations of Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground (Hartford: Ancient Burying Ground Association, 1994), 61.

5Porterfield, 94.

6Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut (Hartford: 1850-1890), 4: 425.

7Jackson Turner Main, Society and Economy in Colonial Connecticut (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 45, 49-50, 91, 194, 2489; William F. Ricketson, “To Be Young, Poor, and Alone: The Experience of Widowhood in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1675-1676,” The New England Quarterly, 64, No. 1 (Mar., 1991), 113-127; Kim Lacy Rogers and Mary Kelley, “Relicts of the New World: Conditions of Widowhood in Seventeenth-Century New England.” In Woman’s Being, Woman’s Place: Female Identity & Vocation in American History (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979), 26–52. See also, Barbara E. Lacey, “Women in the Era of the American Revolution: The Case of Norwich, Connecticut.” New England Quarterly (1980): 527-543, for comparison.

8Daniel Scott Smith, “Female Householding in Late Eighteenth-Century America and the Problem of Poverty.” Journal of Social History 28, no. 1 (1994): 93, 94, Table 3. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3788344

9“Dorothy Hooker Chester, Hartford Founder,” Founders of Hartford, https://www.foundersofhartford.org/the-founders/dorothy-hooker-chester/

10Charles William Manwaring, ed. A Digest of the Early Connecticut Probate Records: Hartford district, 1635-1700 (Hartford: Peck & Company, 1902), 1: 105-106.

11Albert Carlos Bates, Original Distribution of the Lands in Hartford Among the Settlers, 1639 (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1912), 66-67, 105, 308, 479.

12Linda Auwers, “Reading the Marks of the Past: Exploring Female Literacy in Colonial Windsor, Connecticut.” Historical Methods 13, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 204–14.

13Sarah Watters, Hartford Probate Packets, Warren, Joseph-Watson, Jerusha, 1641-1880, 809 – 817.

14Manwaring, 3: 178 (estate of Captain Thomas Hosmer, Hartford, Date of Will: 25 Apr 1732). Italics is added.

15“Colonists of Color: The Moore Family,” Uncovering Their History

African, African-American and Native-American Burials in Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground, 1640-1815 https://www.africannativeburialsct.org/profile/the-moore-family/

16Katherine Hermes, “‘By Their Desire Recorded’: Native American Wills and Estate Papers in Colonial Connecticut.” Connecticut History Review (1999) 38 (2): 150-73, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44369473; Katherine Hermes and Alexandra Maravel, “Finding the Onepennys Among the Wongunk,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut (2017) 79: 95-109.

17‘The Gallows,’ “Uncovering Their History,” https://www.africannativeburialsct.org/profile/the-gallows-the-stories-of-young-squamp-waisoiusksquaw-jack-barney-and-kate/

18“The Minister’s Daughter: The Story of Anne Foster Buckingham Burnham,” Uncovering their History, https://www.africannativeburialsct.org/profile/the-ministers-daughter-the-story-of-anne-foster-buckingham-burnham/