Learning from the Gravestones

Surviving gravestones are the most immediately accessible sources of information about people who were buried at the Ancient Burying Ground since they are still standing and many of the original inscriptions remain legible.

Gravestones represent just a small percentage of those who lie in the Ancient Burying Ground. Few if any were erected in the earliest years. The first generations of Puritan settlers considered grave markers a remnant of the ornamentation of the Church of England, which they sought to purify. And a frontier community like Hartford had little need for the talent of carving gravestones.

When they did begin to appear, even the simplest gravestones were an extremely expensive luxury that only the well-to-do could afford. An estimated one in ten individuals interred in any Connecticut burying ground prior to 1800 had their grave marked with a tombstone.

Many graves, especially of the well-to-do, were marked with both a headstone, which bore the epitaph, and at the opposite end a smaller, plainer footstone, which might bear the deceased’s initials or just decorative carving. In some cases, the headstone has disappeared, but the footstone survives with limited information about the deceased.

It’s unknown how many gravestones were originally erected in the Ancient Burying Ground. Time, neglect, vandalism, and conversion of land to other purposes have led to the loss of an uncounted number of monuments. Weather and environmental pollution have taken a particularly harsh toll, since most grave markers in the Ancient Burying Ground were carved of brownstone from a quarry in what today is Portland, Connecticut. That material is extremely vulnerable to the elements.

In 1835, 563 names were recorded from extant gravestones in the Ancient Burying Ground. These represent an unknown number of stones, since in some cases a single stone had more than one name on it. In 1877 there were 526 stones standing.

Today approximately 422 headstones and 169 footstones are left. Many graves, especially of the well-to-do, were marked with both a headstone, which bore the epitaph, and at the opposite end a smaller, plainer footstone, which might bear the deceased’s initials or just decorative carving. Beneath the open expanses of grass lie thousands of unmarked graves.

In some cases, the headstone has disappeared, but a smaller footstone, placed at the end of a grave, survives with limited information about the deceased.

Mary Skinner, 1772

“Here Lies Interrd ye Body of Mrs. Mary ye wife of Mr. John Skinner, Junr., who Departed this Life May ye 23d A.D. 1772 in ye 42nd Year of her Age with 10 of her Children by her Side who all Died Soon After they ware Born”

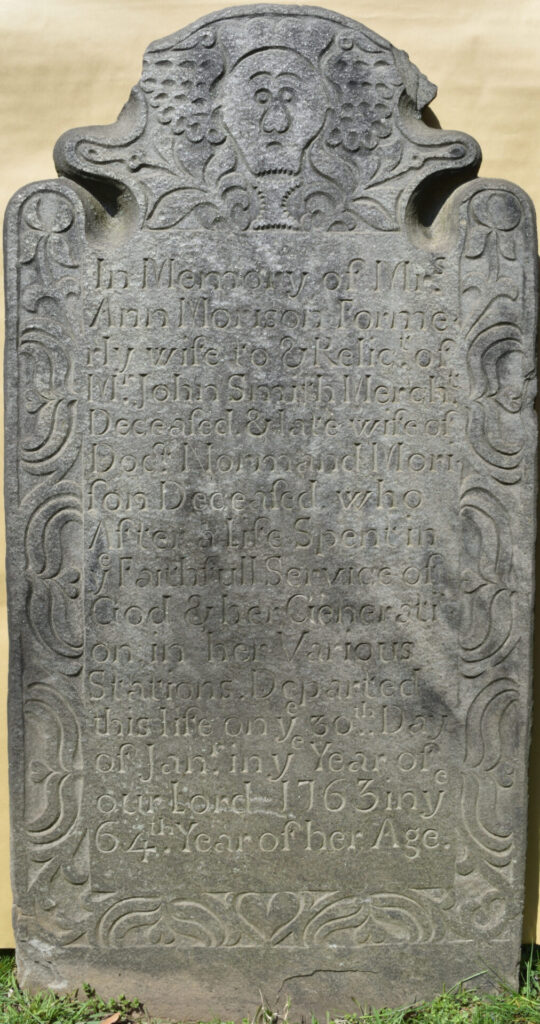

Ann Morison, 1763

“In Memory of Mrs. Ann Morison Forme rly wife to & Relict of Mr. John Smith Mercht. Deceased. & late wife of Docrt. Normand Mori son Deceased. who After a Life Spent in ye Faithfull Service of God & her Generati on in her Various Stations. Departed this life on ye 30th Day of Janr. In ye Year of our Lord 1763 in ye 64th Year of her Age.”